On June 28, the Centre for International Development (CID), a research hub at Harvard University, projected that the economic pole of global growth has, over the past few years, moved from China to India.

The projection was based on the path traversed and progress made by countries in expanding and diversifying their export basket over the years. It captures the accumulation of new capabilities by countries which allow for more diverse and complex production. The latest update to The Atlas of Economic Complexity, based on 2015 global trade data, also ranked 124 countries on an Economic Complexity Index, which could be used by investors, among others, to make growth projections.

According to the new Economic Complexity Index rankings, India is at number 48, having moved up two places from its 2014 position.

China is still far ahead at 26, but has fallen six places in the latest rankings. Japan has led the chart every year from 1995 to 2015, the period for which the rankings are available. The United States ranked 10 in 2015, up from 14 in 2014, and from 11 and 12 in 2013 and 2012 respectively.

India and the African country of Uganda top the list of fastest growing economies leading up to 2025. Both countries are projected to grow at 7.7% annually. China’s annual growth rate is projected to be 4.4% leading up to 2025.

The Atlas of Economic Complexity

Economists and other academics have spent years trying to understand the dynamics of growth. It has gone much beyond the factors of production — land, labour, capital and education/skills. Why some countries grow faster than others is no longer easily explained by the pace of economic reforms, governance, education standards of people, or their skill sets. Not that these do not matter, but despite similar characteristics, some countries have turned more prosperous than others.

Ricardo Hausmann, Professor of the Practice of Economic Development at Harvard Kennedy School and Director, CID, and Cesar A Hidalgo, who leads the Collective Learning Group at MIT Media Lab, have for years studied global trade trends to assess the capabilities of countries. Their research links the ability of countries to acquire and assimilate “knowhow”, and their diversification into other areas of production. Countries that are able to do so can potentially grow faster, they say.

Their research was published as a book, The Atlas of Economic Complexity, in June 2011, with a new edition in 2014. The Atlas itself is an online tool that allows a deep dive into the trade trends of countries in terms of their imports and exports, and how they have diversified or shrunk over the years. Such trends throw light on the nature of industries that may emerge in the countries in the future.

Trade and Complexity

Prof Hausmann sees a strong correlation between a country’s ability to diversify its product portfolio and its ability to gather the knowhow to put together a complex final product, which may require a mix of parts and components.

The American aerospace company Boeing, for example, has a host of suppliers from small and big firms spread across the world. The aircraft may be assembled in the US, but its components come from countries including Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, Italy, France and the United Kingdom. Hausmann’s mantra for growth is to develop the capability to make different forms of knowhow collaborate — it’s the collective of knowhow that will hold the key to producing complex products. The iPhone is another example.

But how do we measure knowhow? Here, Prof Hausmann talks of graduating into products that require more “personbytes” — one personbyte being the quantum of knowledge an individual possesses. And how do we grow knowhow?

It’s a ‘chicken and egg’ situation — a difficult task, Hausmann says. Knowhow is slow moving. A country has to grow its letters, or personbytes. The more letters you have in Scrabble, the more words you can build. You can build your word bank by using letters similar to the letters that you already have. In other words, countries can diversify into related industries once they have acquired specialisation in one.

A country has to aggregate personbytes to create different products, or diversify.

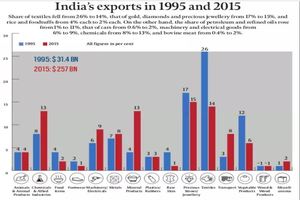

Future Gazing: India’s Personbytes

India is the fastest growing economy in the world today. But its share in total merchandise exports is still minuscule at less than 2%. Total exports in 2016-17 were $ 274.64 billion, up 4.7% in dollar terms. Hausmann’s The Atlas of Economic Complexity does not include services exports; maybe for countries like India this may turn out to favourable, and mean a better rank in the Index. Over the last 20 years, India’s export basket has diversified, but progress continues to be slow. In the five years leading to 2015, the percentage share of the top 10 commodities exported from India dropped to 58% from 60%, according to a study published by the PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry, an industry body, in August 2016. (The higher the percentage, the less diversified a country’s exports.)

These numbers only confirm Prof Hausmann’s theory and research that says knowhow accumulation is slow-moving. Also, knowhow is difficult to transfer.

The latest update to the Economic Complexity Index shows that India is well positioned to continue diversifying into new areas, which include complex sectors such as vehicles, chemicals and certain electronics. India exports 395 products with revealed comparative advantage (meaning that its share of global exports is larger than what would be expected from the size of its export economy, and from the size of a product’s global market).

Add Comment